All the images included in this article are taken by me, therefore feel free to advance any critique.

I first went to Japan in 2012. It was by myself and some of the trips I had were part of organised tours: I deeply enjoyed my experience, but also felt that I failed to get the whole experience that the country had for its visitors.

Last summer I finally managed to organise another trip to Japan: I wouldn’t have been by myself, it would have been for 15 days – instead of just 10 – and we would have also visited Hiroshima – other than Tōkyō and Kyōto which I already stopped at in 2012.

Me and a close friend of mine wanted to get in touch with the rather subtle realm of what we think Japan is like. Such an idea usually involves mostly food and temples, while it rules out the imagery of Japan as a land of dark ages’ warriors, modern buildings and anime. Speaking for myself, the country lays between those extremes, and it resembles what’s depicted by photographers such as Moriyama Daido, Shomei Tomatsu, Nishimura Junku and Hashiguchi George. I think of Japan as a land of narrow alleys, unglorified open spaces and publicly open people.

One of the issues of taking pictures in certain countries is that people mostly avoid having any personal interaction – other than the egotistical ones – in public: people almost never behave spontaneously in the streets. Most of the times, family don’t talk to each other. Children are even scolded just for being playful. It seems as if more than just being appropriate, people are being afraid of being monitored by others and being constantly judged on what they do.

I found such behaviour most common in western countries, although it depends from place to place – even within the same country. Japan – and Iran among few others – is one of the places were people mostly were uncaring about being taken pictures of.

While many people in non-industrailized countries still feel apprehensive when being photographed, (…) people in industrialized countries seek to have their photographs taken – feel that are images and are made real by photographs.

Susan Sontag, On Photography.

What once said by Sontag, nowadays isn’t that much true anymore and it’s hard to be able to take random pictures in the street because anyone – even the smallest person in the frame – could complain about their image being used.

During 15 days I was able to shoot almost 10 rolls of pictures of people around the streets – meaning an equal amount of contact sheets to check, each of which had 36 shots. No one argued or even complained for me taking pictures of any given situation – which would have can actually been understandable. It is common belief that Japanese people are among the most busy people on Earth and they often are considered to be disengaged from human emotions. Other than this belief being extremely superficial, one has to take into account that the clutter of Japanese lifestyle brings along a shallower filter to what people do and say: they don’t care much about being in public and act as they would at their own homeplace. They might be formal, but that’s how most of them also are at home. I find it extremely interesting as it gives me the chance to take pictures of real people.

We left Milan on the early evening of December 26th and landed in Haneda on the evening of the following day (i.e. 12+ hours of flight + time zone). We had to quickly run to the Ōji Station in Kita – a special ward in Tōkyō – as we had to collect the keys to our first Airbnb accommodation. I was starving and managed to find a yakitori-ya in front of the train station. Once at home, I started writing down a daily journal as I did during my sailing trip in Croatia.

Food and map-sketching in my journal are – along with photography, of course – the main activities I underwent while in Japan. I enjoy going to countries to document people’s lives, chill out and eat as if my stomach had no end.

We spent five days in Tōkyō before moving to the next major city in our trip – Hiroshima. While there we managed to visit many of the city’s quarters – Shinjuku and Asakusa always have a speed-track to my heart – and smaller towns such as Nikkō and Kamakura.

We mostly moved by train, as we got the JRP (i.e. Japan Rail Pass). Trains still are atop the most convenient means of transport in Japan. Considering how big Tōkyō itself is, the JR city lines were our only way to move around the city. Even though we had to squeeze in few times, I will never stop thanking the public transportation – as if it were a conscious being – for forcing us to do what I always long for in such trips: living the city as a local.

Trains failed me fewer times than alarm clocks did: for being left ride-less only once – for almost two hours on New Year’s eve night, due to a suicidal attempt on the Yamanote Line – my phone’s alarm betrayed me twice as it didn’t charge up over night.

My plan to visit the Tsukiji Market early in the morning was affected by this mismanagement of technology of mine: I would have had to wake up at about 3:30-4:00 AM, but ended up rushing out of home at 6ish AM, therefore getting there late. It was already very crowded and fishmongers were less central – although still very active – in the market’s life: clients already were the market. What I missed in capturing the workers’ dedication to their activities, I gained in admiring how such actions had to adapt to the early morning ‘mess’ that invades the Tsukiji Market. By mess I mean no confusion or problems: there was no space to move, but my eyes met no frown.

The attitude of adults towards children is a big example of what I mentioned above regarding human interactions in public: kids everywhere usually are silly, as they are just enjoy themselves [A.N. I’m sorry for how obvious I can be]. While in Italy most people would scold them for being bold – still just an example, as it is the country I live in and whose people I know for indulging in such ‘mistake’ – I found many being much more calm and gentle with them, not minding the kids not yet being serious enough.

I went around taking pictures of any situation I encountered. People either ignored me or didn’t even notice it – not out of ninja-like abilities of myself, but out of lack presumption that everyone wants to take photographs of thee. I was even able to get closer to the subject and fill the frame with ease. The result wasn’t just having people being genuine and un-influenced, but also catching glimpses of heartfelt reactions from the people. The kind of look people have when not afraid.

It sure does amaze me that people can be living in fear of what others might think – although most probably I’m not exempted from such automatic behaviour as well. My belief is that there might not be an actual difference in causes when it comes to why people feel like they have to be ashamed of certain aspects of their life, but just in what they end up hiding.

Visiting a foreign country, I end up being fascinated by all the things that are visually most distant and different from what I would normally encounter in my own city – and I do love Milan. An example of that could be smoking areas in Japan: since there are no bins across the cities due to terrorist attacks in the past – as well as other urbanistic reasons – it is forbidden to smoke around the streets. You can find designated areas near the train stations, but they usually are filled with people that are stigmatized for smoking. This is weird for a country were one can smoke in most restaurants, bars and taxis. Still every place got it’s differences and once in another country I tend to notice what my own country is lacking.

Tōkyō welcomed us into Japan as the country nowadays wants to show itself as, but it was with Kamakura and Nikkō that we met the real Japan – although we only visited these two towns as a day trip. Hiroshima was the first city – where we stayed to sleep for few nights – that actually nurtured us, in the ways we hoped Japan would.

First of all, people finally were genuinely weird for us foreigners: while people in Tōkyō would be crazy just for the sake of it or for pretending in front of the tourists, people in the other cities and towns would seem different to us, just because our cultures couldn’t diverge more. Later during the trip, a man in Nara would have told us that Tōkyō is amazing, but it’s not Japan.

While on the streetcar heading towards our second Airbnb accomodation from Hiroshima-eki (the Hiroshima station), we crossed paths with three girls in traditional clothes. They looked nothing like those you might meet in Tōkyō: these were not fake.

It must have been the openness of the people themselves, who are even more easily different from what I left back at home. On the second day in Hiroshima we went to visit Itsukushima – the shrine on the Miyajima island famous for it’s massive orange torī built in the water and completely exposed only when the tide’s low – and met the many fallow deers that inhabit the island. I was taking a picture of two of them horning each other and an old lady was very close to me.

Due to the nature of the lens I use (i.e. a super-wide lens) people usually don’t think to still be in the frame. She still smiled and the picture came out wonderfully – at least according to my personal taste – although I still believe she was more pleased of me taking pictures of the fallow deers, rather than actually acknowledging that she was in the picture. Nonetheless, she smiled and I believe little to no people would have done the same in my home country.

Itsukushima also was the second place where we ate as if we were in a craze: once we got in Hiroshima on the previous day, we headed to the castle for a random walk and came across – completely by chance – with the new year’s matsuri (i.e. festival). There were food stands of all sorts everywhere. We encountered the same in Itsukushima and I never denied any food-call.

Needless to say, I usually travel to take pictures of places and eat.

The island itself was fascinating: despite being a major touristic spot, it retains the mystical aura that is intrinsic to its religious role in the community. This can be said of many other aspects of Japan itself – at least in my opinion: by focusing on the role a given aspect has in the country’s history and society, one can always find how it has been developed to be most integrated and harmonic as possible.

Considering that the exoticness of Japan might deeply influence my judgement, I can still find calmness in it – as long as it’s not Tōkyō’s semi-madness.

The trip to Kyōto came down to being very rushed: we had to wake up at 4AM to take the 6AM train without being in a hurry, but the alarm clock failed us again and we had to look for a taxi in the earliest morning, also first being brought to the wrong train station. Not enough, once in Kyōto I realized that the keys to our Airbnb accomodation in Hiroshima still were in my pocket. Luckily enough, the owner was away for holiday and wasn’t planning to have any customer in the next few days, so there was plenty of time to mail the keys back.

Kyōto’s accomodation was the only non-Airbnb one in our trip. We decided to go for a rented appartment and it was worthwhile: even just the tatami upper floor was enough to give us some days of relax when compared to the more ascetic – although sensefull – choices in the previous days.

I believe Kyōto and its surroundings are the places in Japan were we walked the most. Other than Ginkakuji and Kinkakuji that were easily reachable, we had to hike our way through few paths in order to reach our destination.

I have to admit that few times my lazyness restrained me from getting to the top of the route once I was (self-)convinced that there wasn’t much interesting left ahead.

I indulged in the same mental scheme while visiting the Fushimi Inari Taisha. Once I understood that it would have taken me another 30′ to 45′ to fully climb the hill, I decided to lay back and take my time to shoot pictures of the people around. Such a major touristic spot is sure visited by hundreds of people a day and their heterogeneity comes at help when one aims to document the life of people.

We encountered such diversity also in Arashiyama, a temple neighbourhood outside Kyōto. On our way to Iwatayama – the monkey park placed on a hill in Arashiyama – and back, we met big crowds of people. Due to the closeness to new year’s festival, everyone was very excited and cheerful. I might be simple-minded, but any chance of human interaction is interesting when one wants to capture people’s unspoiled side.

Despite our reluctance, we had to prepare going back home at a certain point. At first, the Shinkansen brought us back in Tokyo, for our last Airbnb accomodation – in Koenji this once. We spent our last two days there and managed to visit the Meiji Jingu – a famous shrine near Harajuku – which we missed on New Year’s eve due to being it too crowded.

Sure we were at fault as we – mostly me – had several courses at sushi Zanmai for dinner that evening, but we also had the luck to end up celebrating right behind Shibuya’s main square, with hundreds of other people: the locals incredibly were completely mental and were climbing first-floor street signs, until the police came to calm them down. It mostly were youngsters, but still it was strange to see.

Japan indeed isn’t either as one would imagine it or as I depicted it in my pictures and in these words. It’s neither black or white, but lies between the lines of what the people that inhabit it are. The complexity of humans cannot be transposed by photographs, but their emanation on one single instant can be documented.

These is a strong parting between what can be seen in a picture and what cannot be even guessed from it. It’s the game of what’s in the frame and what’s left to the viewer’s imagination that’s fascinating about photography: the idea that – compared to a painting, where the author is selecting which stories to tell and which not to, therefore not making them real – a photographer is choosing which voices to listen to and which to ignore, although still existing anyway.

You can never say, do or be everything, and each of us can choose how to face such rather binding thought. Nonetheless, you can always try to say something.

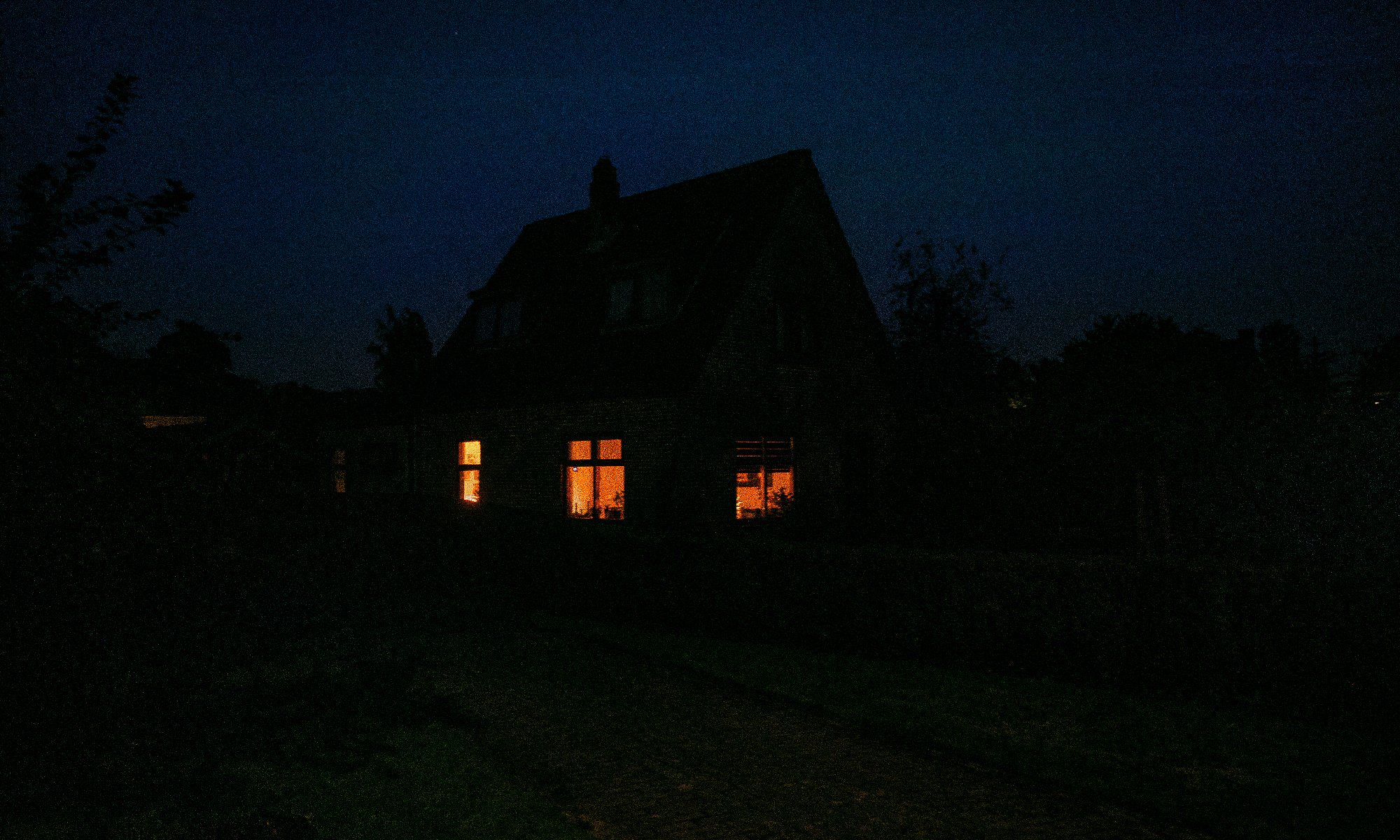

I tried to show one side of Japan. Maybe’s it’s just the Japan I got in my mind and maybe just by luck I was able to get few pictures that completely represent the idea I have of that country and of the feeling I have when there. That being said, I cheer having found something hidden in the dark even if worth notice only by me.

In the real world, something is happening and no one know what is going to happen. In the image-world, it has happened, and it will forever happen in that way.

Susan Sontag, On Photography.

Thanks to Giuditta Fullone for reviewing this article.

All the images included in this article were shot on Ilford HP5 (pushed @1600) film in a Konica Hexar RF with a Voigtlander 15mm ƒ/4.5 lens, home-developed in 1+0 ID-11, printed in a darkroom by Jacopo Anti, and then scanned.